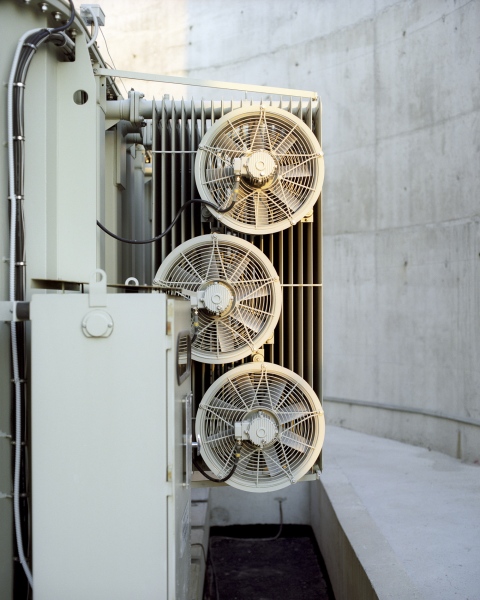

Adriatic Highway is a road that follows the East coast of Adriatic Sea. In a local context it represents a capital infrastructural project which has connected Adriatic territory, and which has played an important role in the development of tourism in Croatia. Opening the road in 1965. has brought direct economic prosperity to many towns in the region, but it has also brought many issues related to aggressive interventions in the cultural heritage and natural landscape. Constructing the controversial road has caused antagonism between urban planners and conservators, whereas today it represents one of the most beautiful roads of the world.

Driving along the highway today reveals fast and intense transformations of the landscape and infrastructure that are made in order to intensify tourism. Mass tourism can be devastating, risky, and eventually low-profit activity. However, lack of choice has forced many people to orientate their activities towards touristic exploitation of their surroundings. Different initiatives are dramatically transforming the landscape on a daily basis in this peculiar environment. As a result, the roads are getting crowded, too many buildings are being built without taking care of integral urban planning, public space is under pressure, cultural and natural heritage is getting devastated.

Natural landscape, architecture and infrastructure have shaped a particular socio - spatial context in which we can trace crossover of economy, ecology and culture, as well as the effect that this intersection reflects on the territory and on the people. Further development of tourism is faced with a challenge of turning the holiday and the experience into a profitable economic resource, but at the same time keeping the authenticity of the present landscape and the way of life on the territory.

Photographic record of the present situation reflects wider social picture, which is important to be documented, since it is in a fast and permanent change. The idea is to create a large sequence that represents imaginary travel along the Adriatic coast. The main motif that connects this whole territory in a literal way, but also the motif that keeps this narrative in one place is the road: the Adriatic Highway.

.

.

.

HIGHWAY FATIGUE

.

Yesterday I heard that some weirdo in Zagreb wrote against the construction of the highway along the Adriatic coast on the grounds that it supposedly corrupts the Dalmatian scenery. Such people need to be medically examined. – Josip Broz Tito, 1962.

Just as Bojan Mrđenović was photographing some of the exhibited scenes, the news spread of the death of the Dalmatian pop-icon Oliver Dragojević. For those few days in late July, it was as if the usual tourist routine had been suspended. The tourists, naturally, stayed their course, but the locals wished they could, at least for a moment, stop the time: grieving, mourning and celebrating Oliver was an attempt to create a collective imaginary photograph. A frame from which all tourists, seasonal workers, traffic jams, and overcrowded ferry ports have been erased. A frame which, beyond the hustle and bustle of the daily life and the looming infrastructural collapse, reveals the "pure" Dalmatia – the one which is faithfully evoked by Oliver's voice and songs.

Even though Oliver himself was more of a symbol of another modernisation and infrastructural achievement – the national shipping carrier Jadrolinija, they were even born on the same year – the construction of the Adriatic Highway was the key precondition for creating the image of the "pure" Dalmatia. Contrary to the opinion to the journalist from Zagreb for whose health Tito worried in the introductory quotation, it was precisely the highway that had transformed the Dalmatian landscape into a cultural fact and resource for creating Dalmatian identity. Of course, the tenets of this identity had existed before – and it also consists of other factors – but the highway organized its formation and the creation of the representation of Dalmatia. It did this in two ways. It has brought tourists and their outside perspective that sees beauty here, and that is why they like it here, and that's why they keep coming. This tourist view is the basis of all those songs and stories about Dalmatia's beauty and uniqueness: they are the ones that "guarantee" this uniqueness with their arrival and their wallets.

As faithfully illustrated by the aforementioned journalist from Zagreb, the beauty of nature and the uniqueness of the coast had been noticed before. It is just that this noticing came from the perspective of class privilege. All those pre-war workers and fishermen did not see the sea or Biokovo as beautiful: for them, the landscape represented strenuous work and a source of food. And to the traditional colonial gaze of the privileged, they were an integral part of the landscape. The journalist did not care about them nor the benefits that the highway would bring them: he only cared about his "aesthetic pleasure". But the highway has democratized this "aesthetic pleasure". In fact, it has made it available to those who had been just part of the landscape. Which brings us to the second way of organizing identity and creating representation. The highway leads to industrialization and tourism development, which in turn distances those who had been part of the landscape from that very landscape as a direct source of food. By securing another source of income, rather than struggling with the land and the sea, they are able to see the land and the sea with new eyes. Only the modernisation impulse – taming nature – allows them to form an image of pure nature and extraordinary beauty, which then becomes part of their identity. Because if their environment is special, then so are they. The snapping sound of tourist camera shutters also endows this identity with international legitimacy.

More precisely, this identity emerges from the tension between modernisation and pre-modernity, whose image has actually been shaped by modernisation. In those few days following Oliver's death, there appeared an unconscious collective wish to freeze this tension, this contradictory identity in time. There was an attempt to eliminate everything that the highway and tourist development had brought afterwards from the frame of this extended exposure. So, what was eliminated? All those commonplace tourist motifs that are difficult to incorporate and that bear an element of peculiarity and dislocation. But they are also the necessary baggage of the "chosen" economic model. This model is a clear context, and all those experiences of the stakeholders involved – from tourists themselves to local people searching for occasional oasis – form an extremely unusual yet comprehensive and interwoven mosaic, which Mrđenović records with his camera, giving an overview of the state of affairs. These motifs are familiar to all of us, regardless of our position: work/vacation, local/tourist. Recalling that feeling of waiting for a bus on a small station on the highway decorated with a Torcida mural, you're watching a family of tourists climbing to their apartment after the whole day spent at the beach and struggling with inflatable beach mattresses and crying children, and asking yourself: What is going through their heads? Are they even enjoying themselves here? Will they be run over by a frustrated delivery van driver while they're disconcertedly crossing the highway?

The key question is how do these dislocated motifs and the dreariness of daily life arise? What is the social frame that makes them possible? What are their origins? At the time when tourism has become the main – and sometimes the only – economic activity in the area through which the highway passes, it is inevitable that various outcomes would result from the attempts of families and individuals to survive and achieve economic breakthroughs in the largely uncontrolled market. All those fittings protruding from concrete, symbolizing unfinished apartments, unpaid loans and bad business decisions, are a normal backdrop to the market battle between small renters and a challenge to the mental Photoshooping of the postcards from our small towns. There are also successful entrepreneurial endeavours, both large and small. The small ones attract attention through sheer bizarreness of the ideas, which can probably only occur to people in the context of market saturation during peak season and the lack of income during off season. At the same time, the larger ones, including the maintained, isolated and inaccessible beaches managed by concessionaires, simply scream social and political injustice.

The second origin is the tourist everyday life itself: organizing and spending your time as a tourist on our coast. Lying in deckchairs for hours, aimlessly visiting famous and less famous sites, and all those tourist rituals that look pointless when you're not a tourist yourself, are necessarily marked by an element of strangeness when observed "neutrally". And the third origin is the seasonal character of our tourism in general. Summer scenes are becoming ubiquitous compared to those that shape life on and around the highway during the winter period. Cars parked in the middle of the empty highway in late October and early November waiting to transport freshly picked olives to an oil mill, dried seaweed on shores and crashing waves, children bundled up and hiding in bus stations from strong gusts of bora while waiting for the bus to take them to school to a nearby town. These winter scenes, which are in stark contrast to the more familiar summer scenes, additionally emphasize the specific ambiance of the summer life along the Highway.

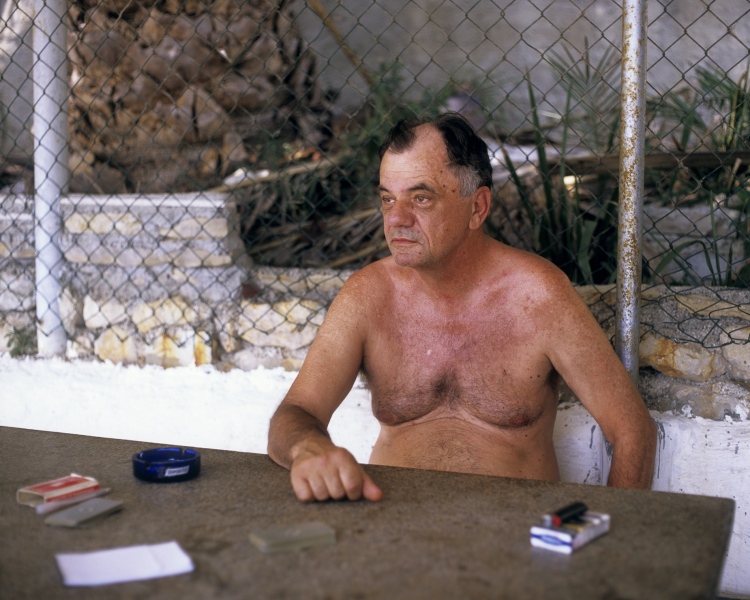

However, someone has to produce this ambiance. As we know from the textbooks that were used at the time the highway was being constructed – the producers of the material world and its effects, bizarrely enough, are workers. The portraits of exhausted workers recorded by Mrđenović bring this whole photo story about tourism and the highway to the beginning, providing a much needed dose of reality – the dose that has been most vividly illustrated by a local seasonal worker a few years ago in a small Dalmatian town. It was the end of August, low season, he had just finished his shift, tiredly sat on the terrace of a café, picked up Slobodna Dalmacija, read a few lines, and addressed the audience: "Now they're saying again that the season has to be extended, that all of us have to work on that. Well, fuck anyone who extends it for even one day!"

Marko Kostanić